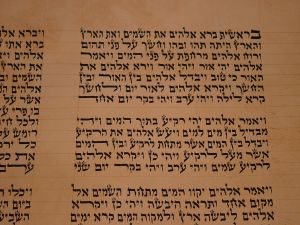

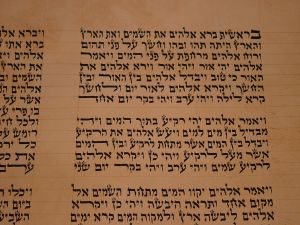

Section of séfer Torá (beginning of párašàt Berēšít) written on gevíl.

(©2005 Gevil Institute of Jerusalem.

Reproduced here with their permission).

Hassafon > |

IMMEDIATE RELEASE:

gawil@globaljms.co.il |

| |

|

Section of séfer Torá (beginning of párašàt Berēšít) written on gevíl. |

Jerusalem, Israel: For the first time in over eight hundred years, “gevíl” (or gewil) sifré Torá are making a comeback in observant Jewish communities in Israel, Europe and the United States. Gevíl is the raw, un-split cow hide used as scroll material after it is processed in accordance with Halakhá. While this process is currently preserved by a handful of Jewish communities in Israel, it fell out of popular usage in the Middle Ages due to a number of historical factors. However, a new revival of gevíl is helping to unite Jews across a broad philosophical spectrum by solving a number of age-old, legal issues about our current séfer Torá. Even the previous Sefaradí Chief Rebbí of Israel Shlit”a is now writing on gevíl. In addition, HaRab and HagGa’ón Rebbí Eliyahu Zilberman Shlit”a insists on it because of the convergence of halakhic (legal) doubts that have been reconciled with its use.

According to one elderly Israeli Rebbí who still processes gevíl in a special pool called a berikhá, “Talmúd Bablí states that gevíl was the exact material used by Moshè (Moses) to write the séfer Torá he placed into the Arón haqQódesh (Holy Ark).” The Talmúd is the oral law studied by observant Jews throughout the world. The Talmud refers to the underlying process used to prepare gevíl as the first legal requirement for the preparation of all kashér sifré Torá. The details governing this process (known as “ibbúd ha’ór”) are very precise.

In 1100 CE, the famous Rambam (Rebbí Moshè ben Maymón) zt”l specifically reiterated the requirements in his well known compendium of Jewish Law, known as the Mishnè Torá. HaRambam said that it is “the law transmitted to Moshè on Har Sináy that a séfer Torá must be written on gevíl.” This is also supported in a section of the Talmúd called Gittín (54b), where we find a second mention that sifré Torá were written on gevíl.

The prescription literally refers to the processing of animal skin with salt, flour and other specific ingredients called meŋafṣím. It is hard to know the exact reasons why these ingredients were chosen. The finished material, when prepared in this manner, is referred to as “gevíl” (pronounced ge-veel or ge-weel by various Jewish groups). Gevíl has a beautiful, leathery appearance and feel.

Unfortunately, most of today’s scrolls are not prepared in this required manner. The Tosafists were probably the first ones to deviate from the required process. The first Tosafists were the famous sons-in-law and grandsons of Rashi (Rebbí Shelomó Yiṣḥaqí) who lived in the Middle Ages. The processing method used by the Tosafists, known as “ibbúd hassíd”, refers to soaking the animal skin in lime, a different substance than what is mentioned in the Talmúd. While this may be okay for the pre-process, to help remove the hair, it has actually taken over the entire process. There is much speculation about why this change took place. While lime may be used to remove hair during the pre-process, the Talmud documents that specific ingredients are required for the process. According to the speculation of one Israeli scholar, this change may have occurred as Jews began to settle in [Central and Northern] Europe after their departure from Italy, as they found a new system of hide making indigenous to the non-Jewish natives. Since they had to contend with guild issues (specifically, Jews were not allowed to be in guilds), they may have purchased a near finished product from their gentile neighbours and then completed the process on their own. This may explain why the European tradition is more lenient with parchment as opposed to the Middle Eastern traditions, where there were no guilds. Regardless of why and when the change occurred, the required process was changed in Europe. In addition, there may have been a deviation regarding the legal non-rôle of gentiles in this process.

Today, there is a quiet debate in the rabbinic world — which is literally for the sake of Heaven. Only gevíl helps to settle an age old argument between the Tosafists and the Talmúd. In the Middle Ages, the full gevíl hide was split to create two separate pieces, as was done in Talmudic times. Each of these pieces had a different term and use (specifically, qeláf or dukhsustós). The debate STILL revolves around which piece is used for writing a séfer Torá or tefillín (known as phylacteries) and which is used for a mezuzá. In ancient texts, haRambam’s determination is that the thin outer layer of skin is known as “dukhsustós” while the thick inner layer (closest to the flesh) is called “qeláf”. This is also confirmed in the Geonic work Halakhót gedulót (743 CE). It is also confirmed by the deuterocanonical Mishná tractate Sóferím. The Tosafists defined these terms in the exact opposite way, by reversing the meaning of the two terms. This makes for a serious legal problem regarding the acceptability of sifré Torá (Torah scrolls) in today’s times, as someone is clearly writing on the incorrect piece. Although most religious scholars acknowledge the original way was according to the Talmudic references, only writing upon full, un-split material — in other words, gevíl — solves this legal issue.

Today, most scribes use one type of parchment for all three types of writing materials (i.e.: gevíl, qeláf and dukhsustós). The parchment is not split in two. Rather, a thin layer is removed from the upper layer, and the majority, if not the entire, lower layer is rubbed off. This produces a very light, paper-like parchment. While this may look nice and weigh less, it has very little to do with the requirements listed in Talmúd Bablí.

The use of gevíl totally removes all doubts about these legal issues without putting anyone on the defensive side. Incredibly, Gewil shows no marks or folds after being folded and is difficult to scratch or mark. This may partly explain why scrolls, such as those found in the ruins of the Judean desert, were able to survive such harsh conditions over time.

For more information about original Gewil scrolls, visit the Gewil website at www.globaljms.co.il or contact their distributor at media@globaljms.co.il to place your order.

Skrivarstuå

–

editor:

Olve Utne

Updated

16 June 2005 -

9 Siván 5765