Through an interdisciplinary study involving musicology, linguistics and history of religion, the goal is to establish parameters for historical performance practice of Jewish liturgical music in Western Europe with the main emphasis on Sefaradí liturgy and music of the Baroque and Classical periods. The study of cross-alphabetical transcriptions will be used to shed light on the historical pronunciation of Hebrew and Aramaic in the environment in question; the study of liturgical variant readings within relevant traditions is hoped to shed light on the cultural genesis and development of the Western Sefaradím; an updated annotated bibliography of Western Sefaradí liturgy and music will serve to facilitate work with the material by performers as well as researchers; and a summary of previous research on relevant aspects of historical performance practice will set the musical parameters for a project resulting in a mini-series of performances of works of Jewish liturgy.

| Goal | Field | Topic | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dissertation | Musicology, historical |

Western Sefaradí & Italian Jewish music |

Primarily descriptive.

Give an overview over Western Sefaradí and Italian Jewish music,

with main emphasis on classical music after about 1600 CE.

Selected sources: Writings of S.W. Baron, Edwin Seroussi, Michael Studemund-Halévy, &.al. |

| Musicology, Early Music |

Baroque & Classical performance practice |

Descriptive/analytical.

Will consist of a general introduction

as well as a specific part treating problems

of particular relevance to Western European Jewish music

from the 1600s to the early 1800s.

Tightly connected with the performance project.

Selected primary sources: Robert Bremner; François Couperin; Francesco Geminiani; Leopold Mozart; Georg Muffat; Johann Joachim Quantz, Ludwig (Louis) Spohr; &.al. |

|

| Linguistics (Phonology; dialectology) Judaic Studies |

Western European Hebrew phonology |

Problem:

Determine the historically and geographically correct pronunciation

for the Hebrew text of relevant vocal works. Method: Analytical: Collect written forms of Hebrew terms in Spanish, Portuguese, Italian and Dutch documents and vice versa. Collect transcriptions of Hebrew from sheet music. Analyse results in light of, e.g., Idelsohn’s works on Hebrew pronunciation. Compare with contemporary Hebrew pronunciation in relevant communities. Selected sources: Ma‘ane lashon; Thesouro dos Dinim; Sefaradí prayerbooks: Amsterdam 1630, 1634, 1636, 1650, etc.; various musical scores in manuscript; Idelsohn, various works. |

|

| Critical/ utilitarian edition |

Religion, Judaic Studies |

Prayerbook for evening services (in progress) |

Description:

Hebrew/Castilian/English parallel text edition

of Western European ritual for evening prayers of

weekdays, Šabbát and festivals, including the Passover Haggadá. Selected sources: Sefaradí and other prayerbooks: Amsterdam 1634, 1650; Venezia 1609, 1719; Livorno 1856; London 1843, 1965; Paris 1994; Guggenheimer: The Scholar’s Haggadah; etc. |

| Concert/s | Music, Early music |

Primarily didactic/interpretative.

Apply principles established in written dissertation

for selecting repertoire, teaching/instructing musicians

and leading concert performance/s of vocal and instrumental

Jewish Early Music. Selected sources: Casale Monferrato Oratorios for Hošàŋna Rabbá 1732, 1733, 1735; Casseres: Leel Elim (Cantata for Simḥàt Torá 1738); Handel: Esther (English & Hebrew versions); Lidarti: Ester (Hebrew); Th. Lupo: Consort music; Marcello: Psalms; Rossi: Širím ašèr liŠlomó; etc. Possibly also extant collections of cantorial manuals and synagogue music from Curaçao etc. |

About 70−100 pp. Will contain the following main chapters:

(Descriptive/utilitarian perspective.)

Architectural description of Western Sefaradí synagogue, including glossary of Sefaradí terms. Some keywords: Tēbá (bīmā, almemmār) normally near west end of sanctuary; main seating in rows facing central axis. Pipe organs may be found (e.g., in Curaçao, Bordeaux, Bayonne and Paris), since ban on musical instruments is not universally practised.

Through comparison of sources from the Spanish and Portuguese tradition with mainly Italian and Aškenazí sources, the Spanish and Portuguese tradition will be defined and put into a historical and geographical perspective. The material used for this comparison will be, mainly, the Friday night service and the Haggadá šel Pèsaḥ. Sources include several 17th Century Dutch editions along with newer British and American editions for the Spanish and Portuguese tradition. For the Italian tradition, sources from Venezia (Venice), Bologna, Livorno (Leghorn) and Trieste spanning from the 16th through 19th Centuries are used; and for the Aškenazí tradition, sources span from the 16th Century to modern times. Additionally, a number of Mediaeval Haggadá manuscripts (e.g., Sarajevo Haggadah, Kaufmann Haggadah) through the 18th Century (e.g., the Copenhagen Haggadah) are used.

Directly textual aspects of interest include: inclusion/exclusion of prayers; variations in main composition of prayers; order of paragraphs and sentences; and niqqúd (vowel pointing). Meta-textual elements of interest include: names of prayers/rituals (e.g., ŋarbít/maŋaríb); and terms for and descriptions of objects, apparel and architectural elements (e.g., tēbá/bima; hēkhál/aron haqqódeš).

Of particular interest is the contrastive analysis of polyglot texts — where one can find important hints about code changes through discrepancies in text or meta-text. As an example can be given Amsterdam 1634, where the Haggadá section tells you in Ladino to take the Apyo (celery) and mojarloha enel vinagre (dip it in vinegar), whereas the Hebrew text has וטובלו בחרוסת (and dip it in ḥaróset). The Ladino text has the newer custom of reserving the ḥaróset for later — in contrast to the Hebrew text, where the older Sefaradí custom of dipping in ḥaróset is preserved. Is this an example of the Hebrew text, even in its instructions, being considered more holy, and therefore less appropriate to change? Or was the editor more fluent in Spanish (Ladino) than Hebrew? Or is this simply an example of juxtaposition of two independent texts with some lack of coordination?

Preliminary studies have shown a relatively high degree of similarity between the Western Sefaradí and the Italian traditions — e.g., in the text of הא לחמא עניא (Há laḥmá ŋanyá). Is this a result of genetic affinity? Or is it mainly a symptom of later influence from one on the other?

The results of this work will be summed up as part two of the Sefaradí performance practice section, and additionally, the full texts of the ritual will constitute the main part of the critical/utilitarian edition (see chapter 2).

A general introduction to the history of Hebrew phonology will be given from the perspective of the Qimḥian school, as viewed appropriate by Churchyard 1999 and supported by the phonological structure of Sefaradí and Aškenazí Hebrew as well as Yiddish.

What is the historically optimal way of pronouncing the Hebrew of liturgical works from specific historical and geographical settings?

There has been a renewed interest in Jewish early Music since the 1960s — as a parallel to the general increased interest in Early Music on period instruments. During this period, there has been much progress in (re)creating a generic “Early Music” performance style. Some elements of this style are historically founded (ornamentation, instrument types), and others are linked very closely to a contemporary sense of what is good taste or feel-right history (low-tension strings, RP pronunciation of English in Baroque music). Amongst significant recordings of Jewish Baroque music from the Early Music movement of the last few decades can be mentioned Jewish Baroque Music (music by Rossi, Grossi and Saladin), played by the Boston Camerata / Joel Cohen, as well as the more recent recordings of music by Rossi by New York Baroque / Eric Milnes and Ensemble Daedalus / Roberto Festa. There is a definite development from the Boston Camerata recording to the New York Baroque and the Ensemble Daedalus ones in the sense of crisper details, a sharper focus on directional sound and a vastly improved intonation. But at the same time, there is basically no development in the Hebrew pronunciation — which on all these recordings stands firmly in the 20th Century Israeli Hebrew-based tradition.

The available historical data include the 20th Century “canonical pronunciation” of Western Sefaradí communities, subdivided in the general tradition and the Amsterdam tradition (Rodrigues Pereira 1994, pp. 39−41).

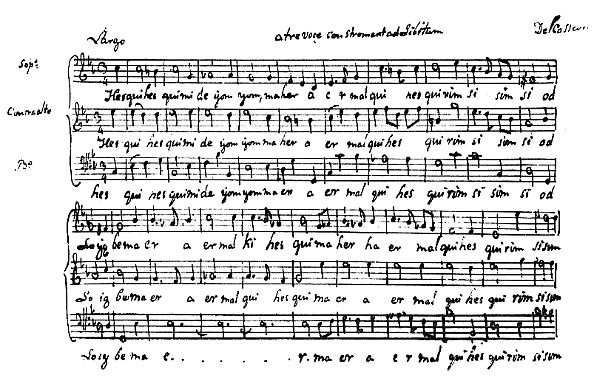

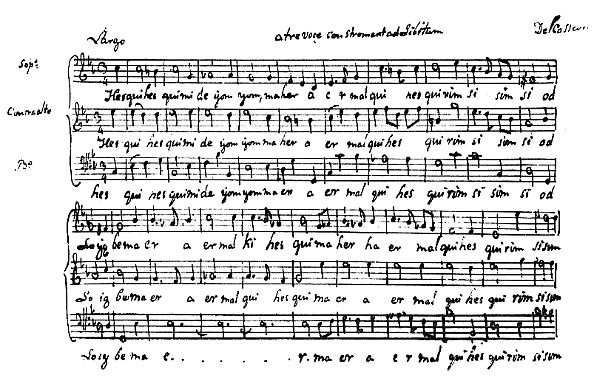

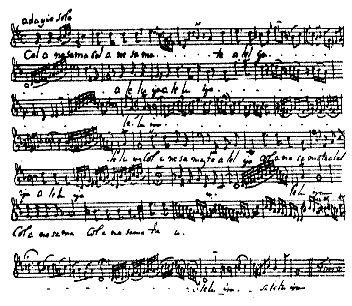

The extant manuscripts of Jewish classical music from the 17th through the 19th Century have, for the most part, Latin transcriptions of the Hebrew text — mainly due to the difficulties posed by different writing directions of Western musical notation and the Hebrew alphabet. This offers valuable information about the pronunciation in the time and place of each of these manuscripts.

In addition to these sources, sources like Amsterdam 1634 (Castilian), Amsterdam 1650 (Castilian), Thesouro dos Dinim (Portuguese), reveal important, albeit less concentrated, information about Hebrew phonology through their transcription of Hebrew and Aramaic words within their non-Hebrew linguistic setting.

A fourth source category in the form of Spanish words in Hebrew transliteration (Uziel 1627) provides a useful reality check, but is of somewhat limited value because of the small sample size.

Data in form of Spanish and Portuguese transcriptions of Hebrew and Aramaic words will be gathered from mainly Northern European sources from the early 1600s until the present time. These data will be entered into a UTF-8-compatible database — probably MySQL (depending on the functionality of the coming version 2.0 of OpenOffice) and thus made available for queries. Interesting questions include:

(Primarily descriptive:) An overview of Western European Sefaradí cantillation of the Torá (Pentateuch) will be given, focussing primarily on the extant sources on the Hamburg, Amsterdam and London traditions. Questions of particular interest in a performance-practical perspective include intonation versus conventional notation, rhythm versus conventional notation, as well as rhythm versus Hebrew prosody.

(Mostly descriptive:) Sefaradí congregational participation versus Aškenazí solo-oriented ḥazzanút ― reflecting in musical structure. Description of tonality, rhythmic structure, ornaments and other general elements.

Aškenazí Orthodox Judaism and parts of Conservative/Masorti Judaism forbids the use of instrumental music in the synagogue as a sign of mourning over the Temple. Traditional Western Sefaradí Judaism is fundamentally different. In earlier centuries, Western Sefaradím are also known to have had instrumental music in the synagogue on festivals, and even on Šabbát — a practice which is currently mostly confined to the liberal branches of Judaism. A brief overview of this field will be given.

Vocal polyphony in the synagogue was very controversial in mainstream Judaism when Salomone Rossi Ebreo composed his polyphonic music for the synagogue with strong moral support from Leo da Modena — and the music was effectively put away not long after it was published. The general tendency has been that polyphonic art music has been avoided — with the notable exception of Western Sefaradím and some Italian and Provençal local environments. In the 1800s, Western Sefaradí and Italian synagogues came to play major rôles in the process towards the use of choirs in the service. Some Western Sefaradí communities have a still surviving tradition of rudimentary non-notated polyphony, mainly parallel thirds or sixths. This tradition is believed to be a worn-down outcome of previous centuries’ frequent use of art music in the synagogue, and Seroussi has shown the tendency for early four-part scores within this tradition to be reduced to three-part scores, and sometimes subsequently to two-part scores or performances.

The Western Sefaradí relatively liberal view in matters of polyphony and instrumental music, combined with a sense of decorum and dignity being a main focus of the service, came to play a big rôle in the shaping of the Jewish Reform movement — a movement which started in Hamburg amongst a mixed environment of Aškenazí and Sefaradí Jews and was subsequently spread to England (London) and USA (Charleston) through mainly Western Sefaradí Jews.

With a basis mainly in Israel Adler’s work on the Amsterdam community, Seroussi’s work on musical variants within the Sefaradí traditions, and Hervé’s work on the Spanish and Portuguese Jewish music of France, a critical summary of the already relatively well-covered general classical/notated music history of the Western Sefaradí tradition will be given. Seroussi suggests that Western Sefaradí music is mostly or entirely a product of musical loans from North African and Ottoman sources mixed with Classical music, Aškenazí music, and secondary internal development/innovation.

The work on variant readings is planned to result in a critical/utilitarian edition (ca 400−500 pp.) of the text of the evening prayers of the Western Sefaradím with thoroughgoing references to the Italian and Aškenazí traditions, including parallel versions of passages that divert in other ways than orthography. Primary sources on the Western Sefaradí ritual include Amsterdam 1630, 1631, 1634, 1650, Amsterdam Maḥzór 1631, London 1965; and Italian and Aškenazí material for comparison and supplement are as outlined in chapter 1.2.2.

The text will contain the following main sections:

Early in the final year of the project, an ensemble will be established (or, if desired, an existing ensemble may be used) for the purpose of implementing the results of the theoretical research. This ensemble, which will hold instrumentalists as well as singers, will work towards presenting the results in a musical performance as described in chapter 4.

A Hebrew Oratorio or two cantatas ― e.g.,

A Jewish weekday evening service based on extant manuscripts from Western Europe (and possibly the Americas).

Sources:

A concert or series of concerts of Jewish music from the Renaissance, Baroque and Classical (and possibly early Romantic) periods. Potential repertoire includes material from alternatives 4.1.1 and 4.2.2, and additionally instrumental music by Jewish composers like the Italian Salomone Rossi Ebreo and the English Thomas Lupo.